Building a Bridge Across the “Valley of Death”: Strategies to Help Support Technology Development

December 14, 2018

HTTPS://STOCK.ADOBE.COM

On Thursday 6 September 2018 at the annual BioProcess International Conference in Boston, the first “Technology Round Robin Featuring Six Innovative Bioprocess Technologies” was presented in an interactive session with attendees as active participants, asking questions and engaging in conversation with the six featured entrepreneurs. Detailed below, this session was a culmination of several steps in an overall strategy for some of the companies participating. To fully appreciate the launch of new technologies into the bioprocess arena, you first must understand the challenges faced by such early stage suppliers and what we can do to support technology development and innovation in support of the biopharmaceutical industry.

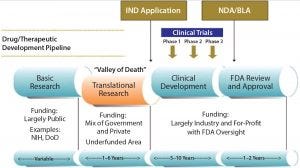

Figure 1: The “valley of death” in biopharmaceutical drug development

Drug development has an identified “valley of death” that comes when the gulf widens between finding a promising new therapy and moving to the necessary clinical trials that can demonstrate its safety and efficacy in humans (Figure 1). Funding does not always keep up with the needs of early drug development, which is characterized by inevitable delays in preclinical data generation or safety results, in early process development, and/or in accessing manufacturing capability. One manifestation of this gap is a lack of growth in new drug approvals despite an over 10-fold increase in inflation-adjusted spending by the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries over the past 40 years (1, 2). Translational research, the term often used for that bridge from drug candidate to human testing, is considered widely to be underfunded and suboptimal (3). That represents a complex factor in the drug development valley of death that impedes the progress of bringing promising new therapeutics to market.

Development Parallels

Herein I refer to “technology development” as that for the bioprocess tools market: companies offering the equipment, supplies (reagents, consumables), software, and emerging new technologies needed by biopharmaceutical companies to increase efficiency and innovate in drug development and biomanufacturing. The dynamic of advancing products to commercialization in this market parallels drug development in one important way: Because of the significant upfront funding required, it is nearly impossible for a company to move a project forward using existing resources. However, early development funding mechanisms such as government-sponsored grants and programs, angel funding, and top-tier venture capital (VC) funding are not nearly as available to early stage technology and “biotool” companies as they are to drug developers. That is somewhat understandable given that VC firms have seen no active initial public offering (IPO) environment for such tools companies over the past several years. Historically, it has been challenging for technology suppliers to achieve exit multiples upon acquisition that reach the typical VC thresholds more commonly seen in sales of biotherapeutics companies. For biotools companies, merger and acquisition (M&A) exits often take longer than anticipated because of slow market traction resulting from the challenges of integrating new technologies into highly regulated good manufacturing practice (GMP) environments.

According to life-sciences and diagnostics investment banker David Wood, “Top-tier VC investing in early stage tools companies has been relatively weak in the past several years compared with biotechnology investment. Outside a few select areas, such as new sequencing technologies that have attracted considerable VC investment at the development stage, many VCs that invest in tools have focused more on growth-equity deals with companies wanting to expand existing commercial footprints and sales. The market has improved somewhat in 2018, driven by exciting developments in areas such as new single-cell analysis tools and an intense focus on technologies that will facilitate the manufacture of next-generation biotechnology drugs (e.g., cell and gene therapies), as well as more strategic investing by prominent players in the space. Despite that improvement, until the IPO market strengthens for tools companies, I still expect the level of top-tier VC investment in their early stage development to remain well behind that of biotechnology.”

That is somewhat understandable given the models followed in the venture world regarding multiples and returns. In the life cycle of technology development, the earliest technology pilot stage, when first proof-of-principle data are collected, usually precedes the development of a commercial prototype, so no customer testing or verification has happened yet. Therein lies the problem: How do you build a working prototype, engage with customers, and test the utility of a technology before you have secured adequate funding? The answer is to focus on activities that will quickly derisk a technology using the least possible time and money to do so.

Why Invest in New Technology?

Howard Levine (president and chief executive officer of BioProcess Technology Consultants) gave a presentation at the AGC Biologics 2018 Global CMO Consultant Summit in Seattle, WA, this past September. “We should fine-tune our approach to manufacturing,” he explained, “to implement new technologies wherever and whenever possible that allow for operational excellence. And we must encourage the development of new technologies to develop a varied and expanding manufacturing toolbox.” When well implemented, such varied and expanding toolboxes can improve manufacturing efficiencies, lower costs, and shorten development timelines. Therefore, Levine argued, the industry should innovate.

As part of Harvard Business School’s Forum for Growth and Innovation, Professor Clayton Christensen is Kim B. Clark professor of business administration. He explains that companies failing to approach new challenges with new business models will not be able to innovate for the future (5). In many cases, a separate work environment, group, or site provides the best way to segregate business objectives, creating a new business model that will be free from the constraints of the existing business.

Technology innovation and adoption in the drug industry can be difficult, however, because of the inherent and understandable bias toward “tried and true” conservative, low-risk approaches. Given the criticality of product-development timelines to the stated mission of a biopharmaceutical company, it is expected that the timeline to an investigational new drug (IND) application dominates senior management’s thoughts and thus determines how teams must spend their time. Looking to other industries, however, we realize that our unique and highly regulated drug development and manufacturing creates a fundamental truth of the drug industry: It is averse to change, and relative to other industries, it is slow to adopt and implement technology improvements.

Figure 2: Dual valleys of death in development of bioprocess technologies (SOURCE: BIOGUIDES LLC)

Suppliers’ Dual Valleys of Death

Over the years, I have faced the technology valley of death when launching new products into critical-path functions in which adoption of even well-engineered products is painstakingly slow. And I have come to realize that the bioprocess technology adoption cycle actually has two valleys of death (Figure 2). The first is perhaps the most obvious: when promising technologies often developed in universities or by entrepreneurs who file a patent or acquire a license on specific intellectual property fundamental to the technology, come to the point at which a lack of funding, market understanding, or clear business strategy causes a slowdown in progress. The initial euphoria of “Hey, this is going to work!” quickly passes as the reality sinks in of the investment needed to complete a product prototype, get it into testing, and refine the product. Without a working technology, it is difficult to collect data, go out to raise more funding, or seek customers — and it is difficult to make a case to the industry that a given technology or tool will have a benefit.

Once that first valley is in your rearview mirror, and the industrial design, full commercial software (if any), and robustness of the new technology have been proven in the hands of at least a few important and influential customers, then it’s time to introduce your new technology to the industry at large. Just when you think you’ve made it, however, the second valley of death in technology adoption looms: commercial product launch. Often it feels like the hard part should be over: Your product works, it had been debugged, the data look good, maybe the industrial design has won an award, and you have a few happy customers. But in fact, the adoption risk is largest to the industry as a whole, and many a sales professional has been blamed for the resulting inability to sell new technology effectively. Perhaps the technology should have been derisked significantly much earlier in the development process (even before the first valley of death)? Strategies for doing that effectively identify the adoption risk before full development of a technology and thus decrease the length of time spent in the dreaded “sales stall.” That should shorten the product adoption time and bring revenue generation as soon as possible.

Strategies to Improve Technology Adoption Success

To decrease the adoption risk of a new technology, suppliers can take a number of steps very early in their development processes. In the early days of biotechnology, the drug candidate you had was one you moved forward. Over time, drug developers began to focus on specific early data that could predict roadblocks in future development and commercialization — e.g., toxicology data, degradation pathways, and manufacturability — to increase the chance that a drug candidate at least would not be stalled by such concerns. Similarly, a series of processes can be applied to bioprocess technology development for increasing its chances of future product success. By focusing early on three related yet distinctive strategies for derisking new technologies, the dual valleys of death can be decreased and sometimes even eliminated.

Strategy 1 — The Fractional Business Development Model: Engage with senior product development, business development, and strategy teams early on.

Early stage technology companies require diligent exploration of different market opportunities, assessment of a potential technology’s fit to market, and a clear business strategy from the beginning. Balancing the demands of product development, hiring, fundraising, and early experimentation with customer outreach is challenging for entrepreneurs and young technology companies. To establish a good plan, an early stage company needs immediate industry contacts; market information; identification of the most accessible application areas; and assessments of market fit, competitive landscape, and timing.

My organization, BioGuides, uses a fractional business development model to accelerate exploration and establishment of sound business strategies often before a technology or product is developed fully. This concept is based on an existing and oft-used strategy for early stage biopharmaceutical companies: fractional chief financial officers. New biotechnology companies pursuing funding need senior leaders who have “been there” before, who know the norms of the industry and can devote a fraction of their time to financial planning and making the necessary connections to approach the investment community. An early stage company cannot afford to hire a professional with such experience full time — nor is it necessary — so a fractional approach of 10–15 hours per week works best.

The same is true for accessing senior business development and product development professionals. You want a team of people who have “been there” before, experiencing successes and failures, and who are dedicated to establishing a long-term relationship with your company as it grows. An emerging company can choose to hire a junior business development or sales person or a consulting firm, which only might have experience in technology adoption. However, a fractional business-development team can save money and get faster results than a single professional could. Accessing part-time senior people with relevant experience can help young companies avoid or get past the dual valleys of death.

Strategy 2 — “Customer-Centric” Development: Young companies should go to customers early for iterative product development, testing, and refinement. One methodology that is much more formalized in the world of large bioprocess technology suppliers is a “survey of needs” or “voice of customer” study to help in setting the direction of technology development and develop return on investment (RoI) calculations for new technologies. Emerging companies need to go to customers even before new products or ideas are fully defined. Steve Blank describes this kind of engagement in his book, The Four Steps to the Epiphany (6). The premise is to undergo a methodical evaluation of what Blank calls “customer development” in parallel with product development. Both activities are integrated, so you do not end up with a “build it and they will come” product-development strategy. If the process is followed effectively, customers will be waiting when you are ready to sell your technology. “You cannot create a market of customer demand where this is no customer problem or interest” (6).

The most notable lesson of a customer-centric strategy is to engage with customers early in product development to gain understanding and refine the messages that will resonate with various customer groups, their problems, and market niches. It is probably better for a small company to seek to “own” a niche with a new technology or service and expand from a point of domination. That has proven to be an effective strategy for launching new products in many cases.

For example, when Tarpon Biosystems was an early stage startup company seeking projects in the area of continuous chromatography, several potential collaborators could have benefited from a stainless, clean-in-place (CIP) version of its BioSMB technology — an asset Tarpon sold to Pall in 2015 — such as insulin and large-scale industrial enzyme applications. But the company decided that first it must own the “single-use” niche of continuous chromatography, given its patent protection and high growth of the market for single-use technologies. What seems obvious now was a difficult decision at the time: to pass on potential funding.

A lesson I have learned is that veering off the intended product development pathway to satisfy a few important customers can be dangerous to the overall strategy of seeking to “own” a niche. Trying to address too many needs in too many markets often leads to delays and overspending on early products for many technology startups. There is a fine balance between exploring all the options available to apply a new technology and the need to pick a path and stay the course.

Strategy 3 — The BioInnovation Group: A consortium of senior industry professionals offers counsel on your new technology.

The BioInnovation Group is an organization of industry professionals who volunteer their time and represent themselves — not their companies — united in the goal of forwarding technology for broad industry use. The mission of this group is to help technology advance by providing industry insights to aid in market application and development. This group was established as a “for-public-benefit entity” with a portion of proceeds returned to its executive members, who donate to causes that are important to the biopharmaceutical industry and for public benefit. Participation is by invitation only, and technology companies pay a fee to come before the group.

The voices of this consortium are powerful, representing years of experience at many different companies: e.g., industry giants such as AbbVie, Amgen, Biogen, Genentech (Roche), Medimmune, Moderna, Pfizer, Shire; major organizations such as the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation; cell and gene therapy companies such as Bluebird Bio and Unum; and emerging companies such as Cobalt Biosciences, Compass Therapeutics, Evelo, and Visterra. If the collective agrees that one application area seems more viable or one strategic direction may speed adoption of a technology, then given the many and varied experiences within the group, that is likely to be correct.

The consortium identifies applications and areas where a technology should have the most impact and — perhaps most important — where adoption should be easiest. Members are committed to benefiting the industry by offering guidance and consultation to technology companies and educating technology providers on biopharmaceutical customers’ requirements. Technology adoption derisking can shorten the customer-input phase (or customer development) and streamline codevelopment and universal proof-of-concept studies in which technology providers maintain their own intellectual property (IP) independence while members of the consortium work together to establish a viable test plan for the associated technology. This is one of many services offered through the BioInnovation Group.

The above strategies all can help shorten the time it takes for a young company or entrepreneur to bring a new bioprocess technology through the customer development process. As more people focus on this as a complement to product development, technology adoption should become easier, faster, and less costly than ever before.

BPI Technology Round-Robin Session

This year’s BioProcess International Conference and Exhibition introduced a new session format in which six new companies participated in a technology round robin. The session began with a panel discussion on the importance of supporting technology innovation. I moderated the session, and the panelists were Thomas Seewoester (executive director and plant manager at Amgen Rhode Island) and BioInnovation Group members Michael Laska (vice president at Cobalt BioMedicine), Derek Adams (chief technology and manufacturing officer at Bluebird Bio), Neal Gordan (chief development officer of Cobalt Biomedicine), and Jorg Thommes (head of chemistry, manufacturing, and controls at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation). They talked about ways that the biopharmaceutical industry can help forward technology. All agreed that new technologies outside the industry should be evaluated and that hearing about new technologies early in their development is helpful to determining their most useful applications. Thommes introduced the BioInnovation Group’s mission and explained that he thought it was a valuable way to encourage innovation in the bioprocess industry.

The round robin of emerging technology companies was conceived during a BioInnovation Group meeting, where participants decided that several companies that had been through the consortium process could benefit from industry exposure. The aim was not to “sell” their technology, but rather to provide a forum of engagement with attendees at the conference. Engaging in this direct discussion was very helpful to several of the attending companies.

Each table at this session was staffed by an entrepreneur and a BioInnovation Group member who served as moderator to keep discussion on track. The audience members rotated from table to table every 12 minutes, which added energy to the room. Each entrepreneur had about three minutes to offer an “elevator pitch” or “shark-tank” style description of the company’s technology to the table audience — for a total of six repetitions. Audience members could ask questions directly of those entrepreneurs, all of whom were either the technology inventors or senior technical people at their respective companies.

Cheryl Huie (cofounder of the BioInnovation Group) later said, “The round robin provided a great forum for BPI attendees and innovation companies to exchange information and investigate the merits and value proposition of emerging technologies. Gaining insight on the possible impact these companies could have on scientific improvements, speed to market, or reductions in cost of goods is like getting a glimpse of what could be.”

The technology company participants were Ran Biotechnologies of Beverly, MA, at Table 1; Covaris of Woburn, MA, at Table 2; Nirrin Analytics of Billerica, MA, at Table 3; TeraPore Technologies of South San Francisco, CA, at Table 4; Elektrofi of Boston, MA, at Table 5; and 4th Dimension Bioprocess of Cambridge, MA, at Table 6.

At Table 1, Roger Nassar (founder and chief executive officer of Ran Biotechnologies) introduced a nanomaterial-based “point of use,” universal, rapid microbe-detection technology with a handheld device. He was joined by BioInnovation Group Member David Fritsch (senior director of strategic programs for the project management office and operational excellence at Sanofi). “The forum was an excellent way to gain attention for our newest product,” said Nassar. “In short, it provides a rapid yes-or-no screening test for live microbes. I was able to provide a quick elevator pitch and obtain immediate feedback from the group, and as a result, my pitch changed over time — and hopefully improved. This interaction already has led to further discussions with a high-profile organization and several potential collaborations.”

At Table 2, Carl Beckett (vice president of Covaris) sat with BioInnovation Group member Michael Laska (vice president of Cobalt Biomedicine). Although Covaris has a thriving business in its Adaptive Focused Acoustics technology for sample preparation and DNA shearing, Beckett was exploring potential new applications of the technology in this forum. “It was a great opportunity to gain exposure of our technology to many industry experts,” he said. “They immediately understood it and identified a number of potential applications where it could be of use in biological processing environments.” At

Table 3, John Ho and Bryan Hassell (principal scientists at Nirrin Analytics) sat with BioInnovation Group member Natraj Ram (associate director of purification at AbbVie). Nirrin has a novel near-infrared (NIR) monitoring solution for biomanufacturing that delivers noninvasive, nondestructive, real-time monitoring of aqueous solutions. “As a customer discovery exercise,” Ho said, “both the roundtable session and the BioInnnovation Group were very effective in introducing us to industry veterans and in exposing the challenges we are facing in commercialization of our technology. Both were invaluable.”

At Table 4, Rachel Dorin (founder and chief executive officer of TeraPore Technologies) and Mary Siwak (TeraPore’s chief commercial officer) sat with Bioinnovation Group member Neal Gordon (chief development officer at Cobalt Biomedicine). Dorin and Siwak showcased a novel, cutting-edge membrane technology for high-resolution nanofiltration using a proprietary and scalable block copolymer self-assembly technology that creates highly uniform precise pores for high permeability.

At Table 5, Chase Coffman (cofounder of Elektrofi) sat with BioInnovation Group cofounder Cheryl Huie (business consultant with Axiom Collaborative). The Boston-based startup seeks to redefine the delivery of biologics by enabling very high-concentration subcutaneous injections using its novel Elecktrojet particle technology. Elektrofi also presented to the BioInnovation Group and learned much from the interaction.

At Table 6, I represented 4th Dimension Bioprocess, a next-generation intensified-bioprocess contract development and manufacturing organization (CDMO) working to democratize access to advanced biomanufacturing platforms. With an emphasis on automation, data analytics, and artificial intelligence (AI) technology, open-source software, and a quality system built to accommodate continuous platforms, the company plans to offer development and manufacturing for biologics. Bioinnovation Group member Tom Ransohoff (vice president and principal consultant at BioProcess Technology Consultants) joined me. “The round-robin setup was a great way to test various business models and do a quick market survey,” he said.

Putting Strategies to Work for Entrepreneurs

Reducing innovation risk by sifting through different technology applications can be challenging if your industry experience is not extensive. The above strategies help identify areas in research, development, and biomanufacturing where particular technologies could offer significant improvements, thus helping to identify target customers. Gaining consultative advice from industry experts who can recommend the steps required to advance your technology in life sciences — and getting assistance with “proof-of-concept” studies — are important in reducing the dual valleys of death and shortening time to market. Early industry exposure and immediate feedback help entrepreneurs set the direction of not only product development, but also customer development.

We all benefit as an industry if technology innovation can be easy, fast, and productive, with as little risk as possible. The next time an early stage technology entrepreneur asks you to take a moment to give feedback in evaluating his or her technology, please remember that you are helping an entrepreneur reduce innovation risk, shorten time to market acceptance, and perhaps increase industry acceptance. You just might help someone get past a valley of death.

References

1 Austin DH, et al. Research and Development in the Pharmaceutical Industry. US Congressional Budget Office: Washington, DC, October 2006; www.cbo.gov/publication/18176.

2 Wood AJ. A Proposal for Radical Changes in the Drug-Approval Process. N. Eng. J. Med. 355(25) 2006: 618–623; doi:10.1056/NEJMsb055203.

3 Manjili MH. Opinion: Translational Research in Crisis The Scientist 10 September 2013.

4 Levine H. Implementing New Technologies in Bioprocessing. 2018 Global CMO Consultant Summit. AGC Biologics: Seattle, WA, 10–13 September 2018.

5 The Forum for Growth and Innovation. Harvard Business School: Cambridge, MA; www.hbs.edu/forum-for-growth-and-innovation/Pages/default.aspx.

6 Blank S. The Four Steps to the Epiphany: Successful Strategies for Products that Win, fifth edition. K&S Ranch: Palo Alto, CA, 2 October 2013.

Lynne Frick ([email protected], 1-978-979-4222) is founder of BioGuides LLC, a Massachusetts-based company focused on accelerating product and technology adoption, and cofounder of The Bioinnovation Group, Inc., a group of industry professionals assessing technology for the greater good.

You May Also Like